From “Kodak Moment” to snapshot

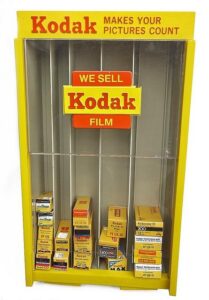

For decades, Kodak was synonymous with photography. The “Kodak moment” became a household expression: a picture you simply couldn’t miss. The brand carried an emotional weight worldwide that few competitors could match. Yet in 2012, it went bankrupt. How can such a powerful brand — one that was literally part of our collective memory — lose itself?

A name that spoke for itself

The name Kodak was invented in 1888 by founder George Eastman. He wanted a short, strong, and universally pronounceable name. Not an existing word, but sounds that anyone, anywhere in the world, could say with ease. The sharp K conveyed strength, the symmetrical structure looked clean, and the word was language-independent. It became one of the first truly modern brand names. It foreshadowed how important branding would become.

The digital camera that never saw the light of day

Ironically, it was Kodak itself that developed the first digital camera in 1975. A bulky device producing 100×100 pixel images, stored on a cassette tape. Visionary, but management mainly saw it as a threat to their profitable film business. The project was shelved.

That single decision illustrates a bigger problem: Kodak saw itself too much as a film producer instead of as a brand shaping memories and visual culture. While consumers went digital, Kodak clung to a product category that was bound to disappear.

The pitfall of a too narrow brand definition

A brand is never just a product. It fulfills functions that evolve over time: from practical recognition to quality label, commercial vehicle, and even societal role. Whoever misses that evolution gets left behind. Kodak had the chance to position its brand more broadly, but remained stuck in the film domain.

Extensions without conviction

Kodak did try to expand: digital cameras, printers, photo services. But these initiatives felt incoherent. There was no clear brand architecture that explained what Kodak truly stood for. Was it a film manufacturer? A camera brand? A service platform? That lack of clarity weakened its perception.

Evolution versus revolution

Brands face moments where small adjustments (evolution) are enough, and moments where only a radical redefinition (revolution) works. Kodak chose too often for the first, while the market demanded the second. That may well be the essence of their downfall: the unwillingness to truly reformulate their brand promise for a new era.

Philips as the mirror image

A striking contrast is Philips. Founded in 1891 as a light bulb producer, but over the decades evolving into electronics, healthcare, and medical technology. Philips consistently redefined its brand promise and broadened its scope. Today, it is a global health and innovation company.

Where Kodak remained trapped in film, Philips dared to leave its product base behind and continuously opted for a broader brand role. The brand evolved with time, without losing its recognition or reputation.

What brands can learn today

Kodak remained globally recognizable, but recognition alone is not enough. A brand must move with new contexts, technologies, and expectations. The failure was not a lack of innovation. The digital expertise was there. What failed was the ability to connect that innovation with the brand strategy.

Today, we still see faint echoes of Kodak: industrial printing, niche applications, even a short-lived flirtation with blockchain. But without a clear brand fit, they remained isolated attempts.

The lesson is clear:

1. Choose a name that is strong and timeless, but let it grow with your brand role.

2. Define your brand by its meaning, not its product.

3. Build a brand architecture that provides direction for new extensions.

4. Recognize when small steps no longer suffice, and when reinvention is needed.

Successful brands don’t make their identity a straitjacket. They make it a springboard. That is the difference between staying relevant for 100 years, like Philips, or ending up as a footnote in a history book, like Kodak.

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)